Two random occurrences yesterday made me aware that the discussion about bepress may seem abstract to some readers here in the Czech Republic or to those who are not librarians, unless you have the time to read through the literature I have referenced. Although: I highly recommend locking yourself away and slowly savoring this referenced literature if you are involved in scholarly publishing, because it is worth it.

Therefore, after relating yesterday’s two small events, I will provide one more analysis of this topic, because recent events do – whatever the future holds – involve all of us, because they reveal problematic aspects of the infrastructure hidden below the surface of all science communications.

First occurrence yesterday: I was trying – really trying – to explain a particular library infrastructure to a research colleague. In describing this infrastructure, my colleague’s eyes began to glaze over, so I stopped my attempt midsentence and fell silent. After a moment, my colleague said thoughtfully: “You know, I still really like [P2P server X]. But there are some books that aren’t there. When I check the library, they are never available [for local idiosyncratic reasons not directly relevant to this post]. You know what would really be helpful? Having those books.”

Second occurrence: My mom told me she reads the post and does understand it, though not all the technical phrases.

Therefore, I will try to provide an analogy of recent events here that might make sense to anyone, using Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (you see, my mom loves mysteries and will relate).

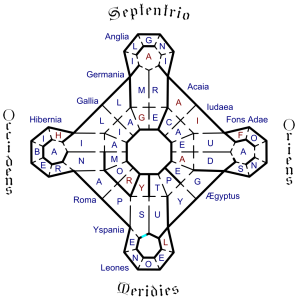

Deep in Italy, in the year 1327, curious events take place at an abbey. An abbey which has a mysterious library, the Labyrinthus Aedificium:

This library, storing knowledge from across the ages and from all corners of the world, has come under the rule of Jorge from Burgos, who has closed the library to the public (to put it in modern terms) and is particularly concerned about access to Aristotle’s Poetics, Book II, on Comedy. A representative of those who believe in logic, Brother William of Baskerville, investigates this “gated library” situation, in which Jorge is willing to murder anyone trying to gain access to the legendary Aristotelian book and its (in his eyes) inflammatory content.

In the end, the Labyrinthus Aedificium is burned to a crisp, but other libraries remain – although no one knows if there are additional Poetics, Book II copies. With or without Comedy, humankind’s legacy of scientific knowledge remains intact because of a redundant system (i.e., multiple copies of physical manuscripts) held beyond the grasp of any particular Jorge(s) of the day.

In today’s world, increasing amounts of scientific knowledge are stored exclusively in electronic format. One could consider these networks to be a kind of virtual Labyrinthus Aedificium; the data, its manuscripts.

Who controls these networks, controls access to their content.

Less diversity in ownership of these networks increases the likelihood of a modern day Jorge shutting off access to things he (or she) simply doesn’t like.

While today’s academic IT and library infrastructures are still quite redundant, the acquisition of infrastructure tools and content by fewer players (let’s forget the commercial or non-commercial aspects for a moment) worries those of us who believe in redundancy and in academic libraries as being neutral protectors of humankind’s scientific legacy.

Looking in the mirror this week, we librarians were asking ourselves: have we been doing enough to protect the past, present, and future infrastructure(s) for scientific communications? This is a very big question.

Additional Reading

Eco, Umberto. (1983). The Name of the Rose.